- A church capital budget helps you assign values to projects and prioritize which projects should move forward

- The costs of assets, expected benefits (revenue), and ongoing cost (savings) help determine the viability of a project.

- Net present value (NPV) and the profitability index (PI) are the primary outputs of church capital budgeting. Other outputs can help paint a picture of project desirability too.

Church capital budget explained

Now we’re getting into my wheelhouse.

Like I said before, I don’t pertain to be the greatest guru of the soft skills (mission statement, SWOT analysis, strategy formulation) covered previously. But now…now we’re breaking out the spreadsheets, and I can promise you that I can help you solves some problems when it comes to finances.

Church capital budget template download

Want to play around with the example used in this post?

Complete the form below and click Submit.

Upon email confirmation, the workbook will open in a new tab.

What is a church capital budget?

You might not know what capital budgeting is. That’s fine. When the average person hears the word “budget” they think of what money comes in during the month (sales, income, contributions) and what money goes out that same month(expenses). That’s an operational budget and we’ll cover that in a little bit.

Capital budgeting is the process by which an organization chooses which long-term projects to invest in. In a business setting things such as the time value of money, depreciation, and taxes are taken into consideration.

Capital budgeting for churches vs for-profit businesses

When conducting capital budgeting for business, projects are typically ranked based on their forecasted profitability. The projects that are thought to be the most lucrative are usually prioritized.

However, since churches are nonprofit, we’re going to have to attack this from a slightly different angle. Some projects might bring in more members and therefore more money. Other projects might help to achieve the church’s mission, but not bring in a dime. If that’s the case, we’ll have to consider other types of value besides cash money.

Capital budgeting is designed for for-profit organizations. However, with a little creativity, we should be able to tweak the process so that your church can use this powerful tool too.

You’ll be able to quantify what you foresee the expected returns to be on the big projects you want to undertake. You’ll be able to rank projects and choose how you employ your scarce resources. Best of all, you’ll be able to make wise decisions that will lead you closer to achieving your mission.

How to create a church capital budget

Big goals sometimes require big projects

Taking into consideration all of the previous steps you’ve completed in the strategic planning process (mission statement, SWOT analysis, and strategy formulation), think about what large-scale projects will need to be undertaken in light of your future plans.

Some things have probably already come to mind. Don’t systematically dismiss a particular project just because it seems infeasible. The point of the capital budgeting process is to make it obvious what projects you should pursue. So, all you’re sacrificing by running a project through this process is a bit of time.

Ultimately, you’ll want to select your projects and move on, so you can’t let this step drag on forever. But, if a project potentially plays an important part in your strategy or would help you achieve your mission, then, by all means, give it its time in the sun and then decide if it’s feasible or not.

With a list-in-hand of the projects you want to explore, let’s move on to crunching numbers.

By the way – all of the numbers you input into this workbook can be changed. So don’t overthink/over stress about any of this!

What church project will we be using as an example?

For the example used in the screenshots, we’ll keep it simple. The project will be a parking lot addition.

Our hypothetical church is seeing that membership has outgrown its existing parking resources. Many members are forced to park on the street during service. Additionally, the church leaders hope to keep the recent rate of growth up and they want to provide their members with plenty of room to park.

In light of this, they have decided to use some of their undeveloped land to add an additional 52 parking spaces.

Disposing of assets – is something being replaced?

If you’re replacing an old asset with a new one then you’ll have to input some information about the old asset. Why? Because even though an asset is being replaced, cash flow in the present and future can be affected. It’s cash flow that gives us your net present value (NPV) and NPV is how you (mostly) prioritize new projects.

*If this is starting to get too technical for your taste – hang in there. These terms will be explained in a simplified manner. Leave a comment if you have any questions.

Fortunately, for a church, the only thing we need to know about the old asset is what it can be sold for today. Since churches don’t pay taxes, none of the other information matters. Not even the original cost. Why? Because it’s a sunk cost.

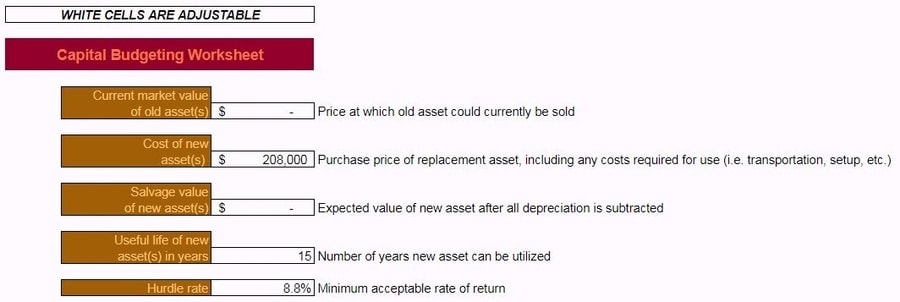

So, if the old asset can be sold for cash, enter a value in the Current market value of old asset(s) field.

Disposing of assets – church parking lot

In our example, something new is being created. There’s nothing old to dispose of. Even if we were replacing an existing parking lot – old parking lots don’t have much value to anyone else.

So, in this example, the Current market value of old asset(s) is $0.

If, when you’re analyzing your church’s capital projects, you have an existing asset that might be worth something – enter the market value here. Whatever you can sell the old asset for will help offset the cost of the new asset. This will help increase NPV.

What is a sunk cost?

Sunk costs can be tough for people to grasp and even tougher to act upon.

A sunk cost is one that’s already been incurred and should have no bearing on future decision making. Meaning – the cash has left your hands and there’s nothing can be done about that anymore.

That’s not always how people feel emotionally, but from a strictly logical standpoint – it’s true. Money spent in the past is already gone. It cannot be unspent. Only cash flows in the present and future matter.

So, if you find yourself making decisions (in your personal life or on your church’s behalf) based on the money you’ve spent in the past – you need to stop and check yourself. Realize that nothing you do now can fix those mistakes. Base your decisions on what you can control now and in the future.

Initial cash outlay

First and foremost, what’s the new asset going to cost?

Include every expense that will need to be incurred to get this asset into service. Taxes, fees, shipping, labor…everything. These extra costs can add up and can significantly affect your decision making, so be sure to include them all.

Enter the grand total into the Cost of new asset(s) field.

Initial cash outlay – church parking lot

In our example, we’re estimating the total costs to be $208,000.

This will be enough to cover not only the parking lot itself but the design and ancillary costs too.

What will the salvage value of that new asset be?

Thinking about what your brand new asset might be worth when you’re done with it might seem silly. It’s so far in the future – and so hard to guess at, why bother?

Well, it is far into the future and you really can’t know what it’ll be worth. But, it will matter. Especially if it’s a higher-cost asset. Even if it will have no value in and of itself, will the scrap be worth something? Will your church be able to get anything out of this asset when it’s reached the end of its useful life?

You’re not going to be exactly right about what it’ll be worth, and that’s fine. Here’s a little trick to get you in the ballpark – start out with a number that’s absurdly high. Then, come up with a number that’s absurdly low. Start working your way back from the high number and up from the low number. When you feel like you’ve reached something feasible – go with it.

If you can’t settle on one good number then average the two numbers out if you need to. Just make sure you’re comfortable with the number when you’re done. It’s always best to be more conservative with forecasting than liberal. This gives you a margin of safety.

Once you’ve got your number, enter into the Salvage value of new asset(s) field.

Salvage value – church parking lot

Again, parking lots aren’t really worth anything to anybody else. So, unfortunately, we’ll have to enter a salvage value of $0.

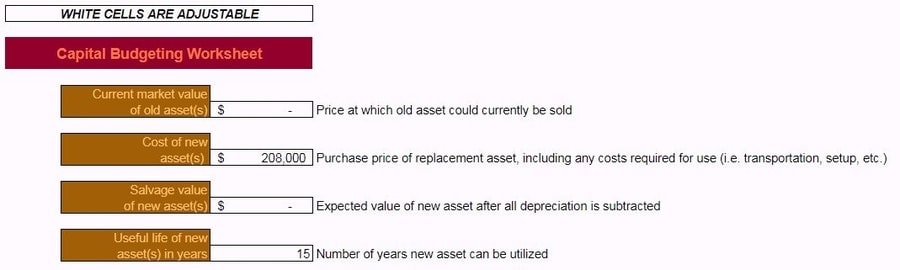

What is the new asset’s useful life?

An asset actually has two different life spans. A depreciable lifespan and a useful lifespan.

What’s the difference?

An asset’s depreciable lifespan is the number of years an asset will take to be “written off.” Depreciation is a concept created by accountants. What it does is spread the cost of an asset over many years rather than having it hit only one year.

For example, say a company bought an asset for $50,000 with a depreciable life of 10 years. Rather than having that expense hit the year of the purchase, they would charge $5,000 to their income statement for the next ten years. The cost is spread out – not swallowed all at once.

Confused? No worries. Since you’re doing capital budgeting for a church, and aren’t subject to income taxes, you don’t have to worry about depreciable life (at least as far as the capital budget is concerned).

Okay…what about useful life? Well, depreciable life is for accounting in income statements. It’s roughly accurate but doesn’t really have any correlation to how long an asset can really be used. An asset’s useful life might be shorter or much longer than its depreciable life.

It can be hard to say how long an asset might really be useful. But, you have to put forward your best guess. I usually recommend that forecasts err on the conservative side.

Since a longer useful life will mean a higher value, I suggest you enter a value in the Useful life of new asset(s) in years that is on the low side. Start at 1 year (if an asset has a useful life of less than a year, it probably doesn’t belong in the capital budget) and work your way up. Once you hit a number that isn’t on the absurdly low side, you’re probably pretty close to a nice and conservative estimate.

Useful life – church parking lot

A quick Google search reveals that the expected useful life of a paved parking lot is 10-15 years. Since our example church wants to get the most out of its investment, we’ll enter a useful life of 15 years. This will require a commitment to proper maintenance and will cause the church to incur additional costs – which we’ll address later.

How much of a return does your church want on its capital projects?

Time, money, and other resources are limited. Not just for you and your church, but for everyone.

In order for a project to “make sense,” it has to eclipse a minimum acceptable rate of return.

For instance – if your church was presented with the “opportunity” to invest $1,000 and you were promised $1,050 in ten years, you would probably pass. Why? Because it’s just not worth it to tie up that $1,000 for a decade and to only receive 5% (about .5% per year) back for doing so. That money could be used for something more worthwhile now.

So, you might not know exactly what your hurdle rate (minimally acceptable rate of return) is, but you probably know it’s more than .5%.

If your church borrows money, keep in mind what you’re interest rate is – you’ll want your hurdle rate to be at least that much. Otherwise, you’re not getting a good return on investment on that borrowed money.

Other than that, I can’t say what your hurdle rate should be. This is a very subjective thing. Every church will be different.

I would recommend that you undertake the same exercise I suggested for determining the useful life of the asset – start at 1% and work your way up. Once you say “okay, I suppose I could live with that return,” then you’re probably in the neighborhood of a practical hurdle rate.

If you want to be a little extra conservative (and I would recommend as much) then go ahead and tack on a little extra to your rate. For instance, if your hurdle rate is 5%, maybe up it to 5.5%. If it’s 8% consider increasing it to 8.8%.

This tiny increase puts just a little more pressure on your projects to perform better in order to be accepted.

When you’ve finally settled on a hurdle rate enter it into the Hurdle rate field.

Hurdle rate – church parking lot

The rule-of-thumb is – the riskier the project, the higher the hurdle rate.

A parking lot might not seem like a particularly risky project. But, as you’ll see, justifying its construction is contingent upon church membership continuing to increase. That might seem likely for our example church, but it’s no sure thing.

An 8% hurdle rate seemed reasonable under the circumstances. However, that was bumped up to 8.8% to provide a little more room for error on the part of the projected cash flows.

The most important part of a church capital budget – the forecasted cash flows

As I’ve mentioned before – investments are defined, ultimately, by three variables. Cash in, cash out, and time. Notice I said “cash.” Not sales, not promises, not receivables.

Cash.

This step involves all three variables. Cash flow out, cash flow in, and the timing of each.

Cash outflows

Most projects will incur more costs than those required up-front. Many times costs are necessary as a part of the ongoing project.

The types of costs can vary. Here are some ideas for ongoing costs that a church may incur as a result of undertaking a new project:

- wages and fringes

- maintenance

- utilities

- supplies

- insurance

- interest

- leases

- advertising

And on and on…

I cautioned you to not overthink any of these steps earlier, and I stand by that. However, make sure you think this part through thoroughly. Overlooking expenses and not including them in your church capital budget can make a project look more attractive then it actually is. You don’t want to be ten years into a project and realize that there were expenses you never accounted for.

Next, think about the timing of the expenses. Are they monthly, weekly, yearly, or erratic? The capital budgeting worksheet is set up to look at cash flows yearly; not monthly or weekly. So, if monthly or weekly cash flows are expected, you’ll have to multiply them by 12 or 52 respectively.

Finally, keep in mind that costs tend to rise over time. A capital budget forecasts many years into the future. What cost $100 today could cost $125 or more fifteen years from now. Be sure to account for inflation – which traditionally runs 1% to 3% per year.

The future cash flow worksheet

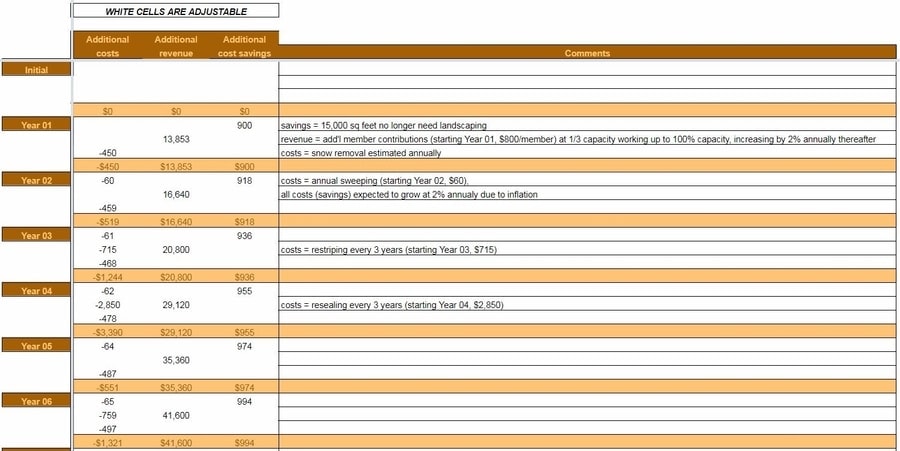

The Future CF Worksheet is a scratchpad you can use to itemize costs, revenue and cost savings. None of the information entered here will affect the rest of the workbook.

Use the Comments field to enter your own notes about the expected future cash flows. This is useful because you can refer back to this information if you ever have a “what was I thinking…” moment.

Once you feel you have a sound (conservative) forecast of the cash outflows, enter these amounts in the Additional costs column. Keep in mind that these values need to be entered as a negative number. Don’t worry about messing that up, though. The workbook has data validation rules that will prevent you from entering a positive number in this column.

The capital budgeting workbook is set up to only accept Additional costs for as many years as you said the asset would have a useful life. So, if you entered “15” as the Useful life of new asset(s) in years, you can enter 16 years worth of expenses, but Year 16 won’t be included in any of the calculations.

Cash outflows – church parking lot

More parking lot means more parking lot maintenance. For starters, I assumed that there would be additional costs for snow removal every year. This was estimated to be $450 in Year 01 and increase by 2% every year thereafter.

If this were a real church performing this capital budgeting, I would caution them to not enter their entire expected snow removal expense here. The costs tied to the existing parking doesn’t matter in this analysis. They’re going to pay that anyway. Only expenses (and revenues and savings) tied to this project should be considered.

Parking lots also need to be restriped to keep them looking good and resealed to keep them from deteriorating.

Restriping was estimated to take place every three years starting in Year 03. This cost was also expected to grow at 2% annually, or 6.1% every three years.

Resealing was expected to take place every three years starting in Year 04. The cost was expected to be $2,850 at that time and then, you guessed it… increase at a 2% annual rate.

Okay, we got the negative cash flows (the costs) out of the way, let’s move on to the cash inflows.

*This is a long post. Click here to read Page 2.