- Download the free template by filling out the form below

- Estimate the amounts and timing of cash inflows

- Forecast the amounts and timing of cash outflows for expenses and capital projects

- Determine a desired ending cash balance for every month in the planning period

- Factor in the effects of short-term and long-term financing

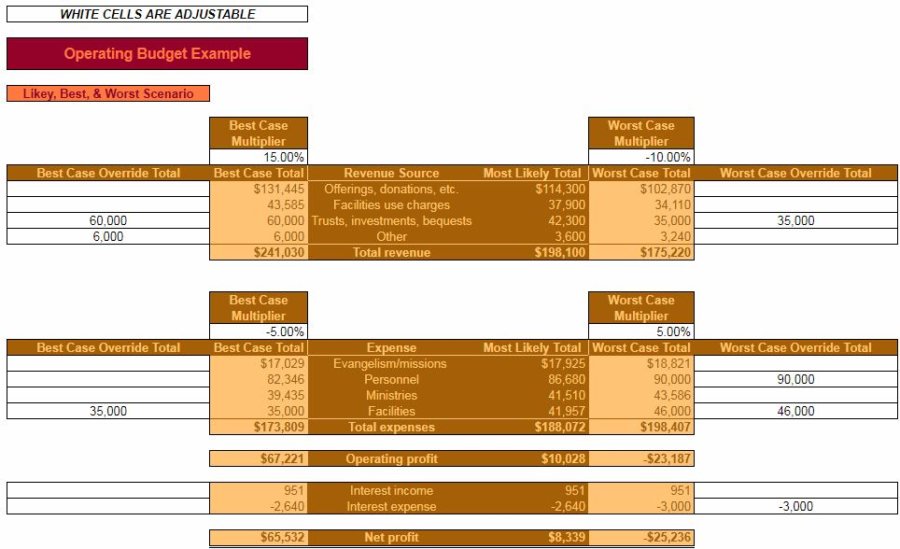

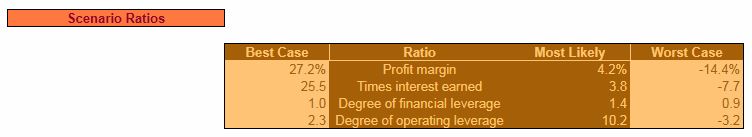

- Analyze the most likely, best-case, and worst-case scenarios in your financial statements

Get your copy of the church financial budget template

Complete the form below and click Submit.

Upon email confirmation, the workbook will open in a new tab.

Sample church financial budget to help your congregation reach its goals

All right, we finally made it! This is the third post on church budgeting. It’s also the sixth, and final, post on church strategic planning. Yes…this is long overdue.

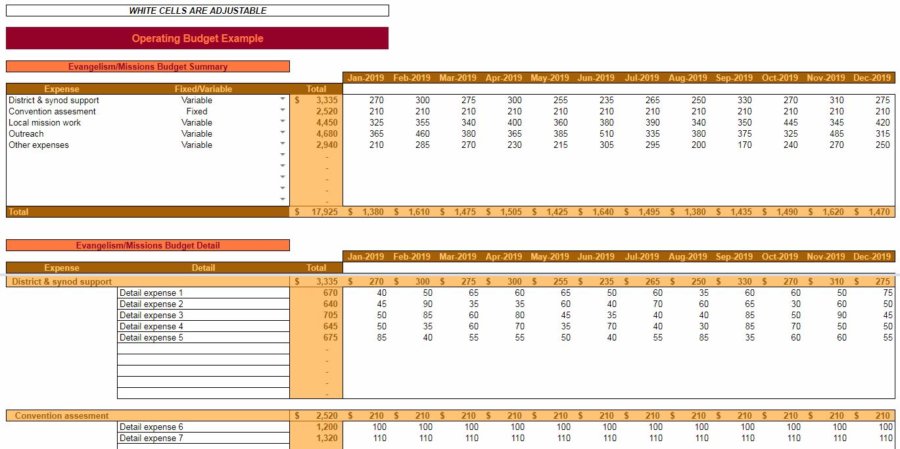

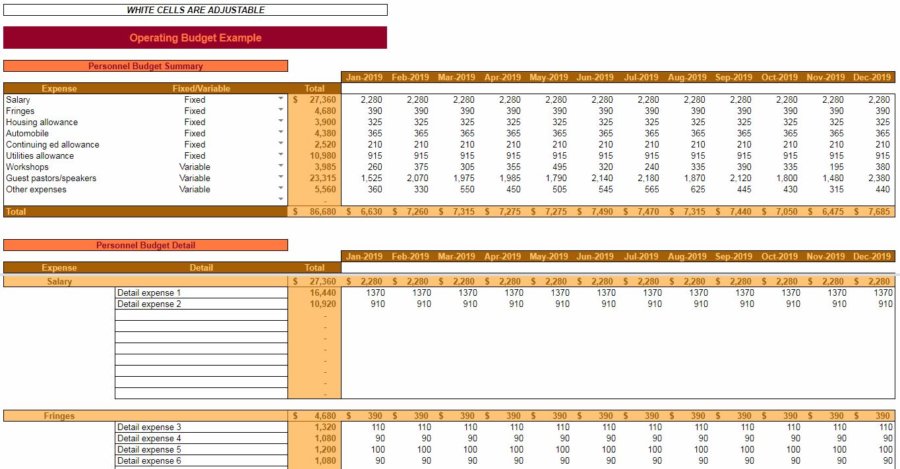

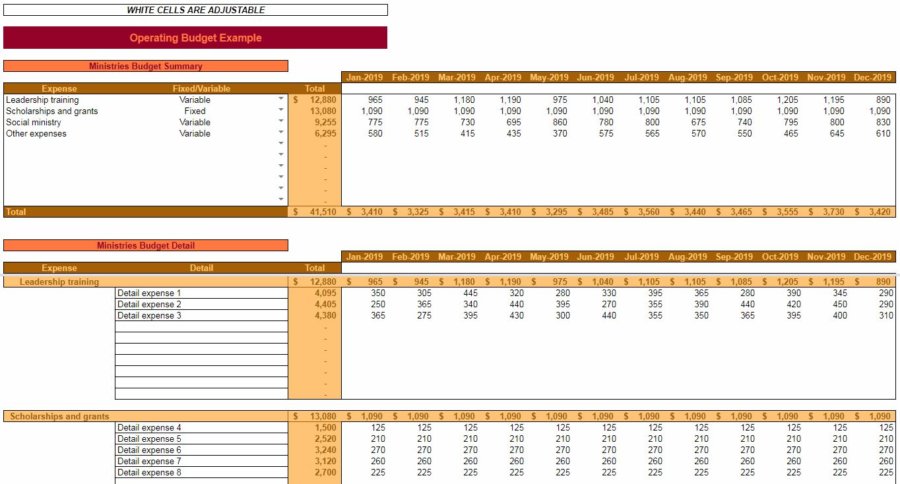

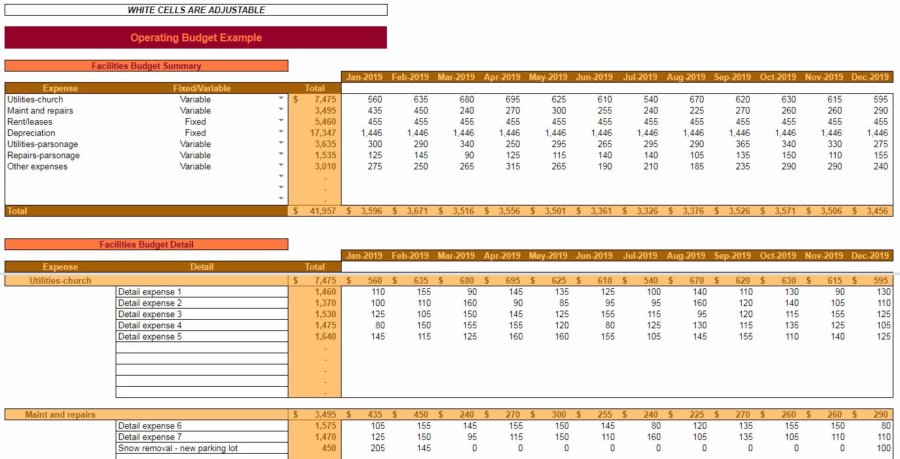

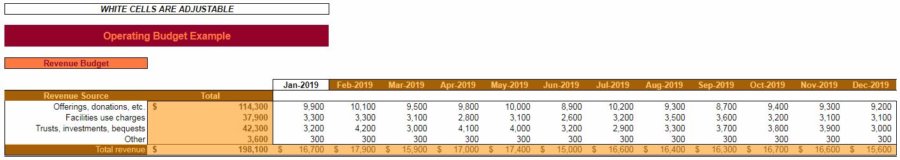

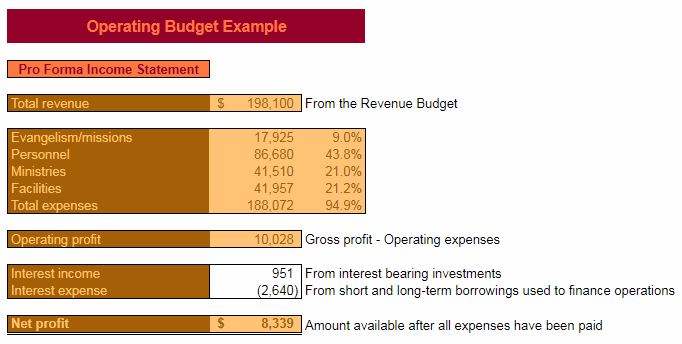

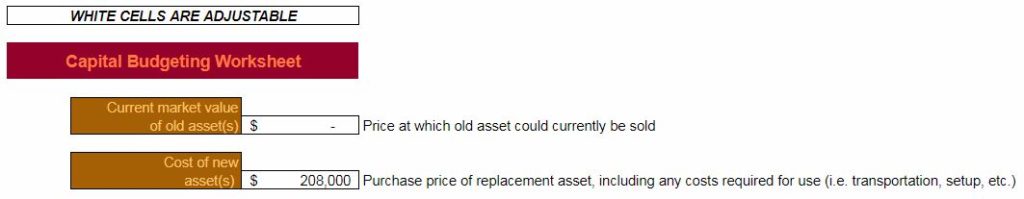

Capital budgeting for churches was addressed previously. As was creating an operating budget. The capital budget involved the forecasting of cash inflows and outflows from the installation of a new parking lot. The operating budget involved estimating revenue and expenses to arrive at a pro forma (estimated) income statement.

Does your church have big capital projects? Read this post:

CHURCH CAPITAL BUDGET – WHY IT MATTERS & HOW TO DO IT RIGHT

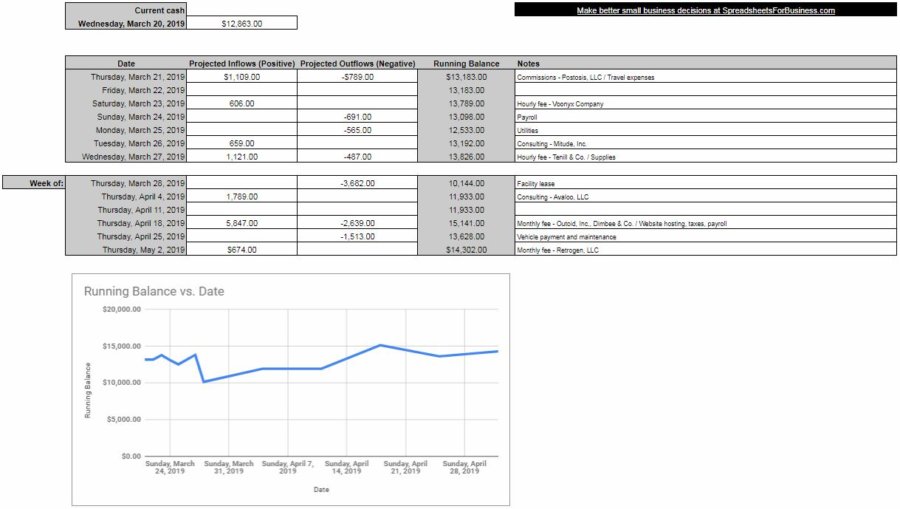

The financial budget builds off of the operating budget. It allows your church to estimate the timing of cash inflows and cash outflows. Doing so will help ensure that your church doesn’t run up against a cash flow crunch throughout the coming year.

Yes, strategic planning is time-consuming and labor-intensive. Never more so than the first time you do it. For the church that is serious about ensuring the ongoing fulfillment of its mission, it is time well spent.

What is a church ‘s financial budget?

A church financial budget walks through the expected timing and amounts of cash receipts and expenditures over the course of the next year. Churches are in a unique (and somewhat enviable) position since most of their revenue comes from donations. They typically receive cash instantly.

One exception, for the church, might be Facilities use charges, or something similar. Revenue like this is often paid in advance to reserve dates and times. Since the cash comes in earlier (typically) than when the service is delivered, there could be a situation where cash flow and revenue recognition are different.

On the cash disbursement side, a church faces a lot of the same issues as a for-profit business. The recognition of expenses could be different from when the actual cash leaves the church’s checking account.

The church’s Cash Collection Schedule and Cash Disbursement Schedule will come together into a Cash Budget. It is here that the church will have the opportunity to adjust the Desired Ending Balance. And to make any tweaks to Short-term or Long-term Financing arrangements.

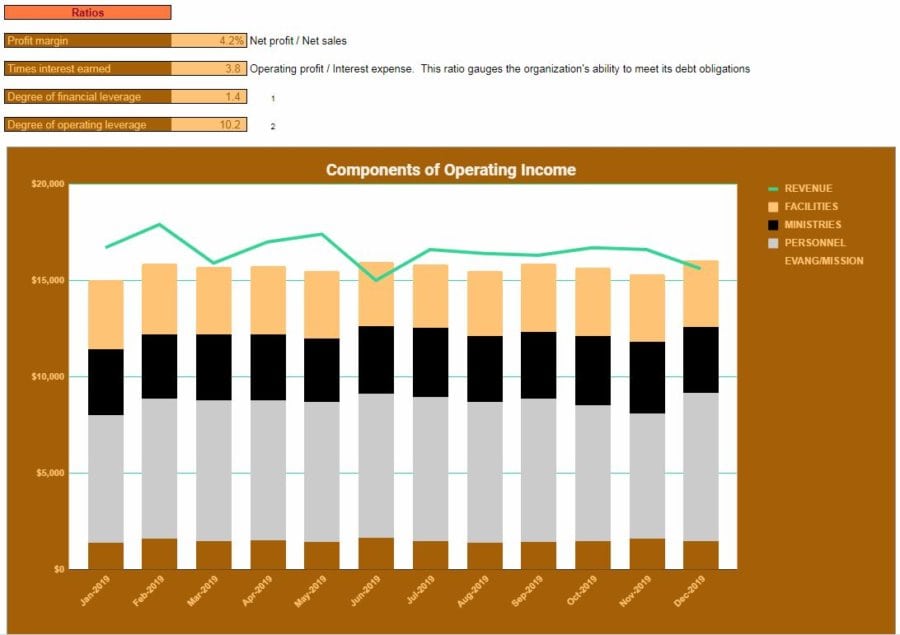

Everything culminates with Pro Forma (expected) financial statements. Just as with the operating budget. This allows the church to compare where they start the year with where they end it. With this information, Ratios can be calculated. More importantly, needed action can be taken to hedge potential problems.

Also, a chart illustrating the month-to-month changes will be available. Also, your church will have the opportunity to play with best-case and worst-case scenarios.

The importance of a church financial budget

Cash is the lifeblood of a business, and a nonprofit organization is no exception. All strategic planning plays an important role in preparing for the future. However, none of the steps may be more important than the financial budget.

Failure to plan for potential shortfalls in cash could mean shuttering the doors. I could mean forever forgoing the opportunity to lead your congregation to the achievement of its mission.

How does a church’s financial budget differ from an operating budget?

A

Want to compare a church financial budget and operating budget? Read this post:

CHURCH OPERATING BUDGET TEMPLATE (FREE) WITH WALKTHROUGH

Operating at a loss in a particular month (e.g. having more expenses than revenue) won’t necessarily constitute a crisis in your church. It can’t go on forever, but if it’s a short-term problem, you should be able to push through it.

But, having more cash go out than comes in during a given month will obviously deplete your cash on hand. Beyond that, if the difference is big enough, and goes on for long enough, your church will be in real trouble.

Cash is king

You don’t pay your bills, or your employees, with numbers on a spreadsheet. As great as spreadsheets are, they can’t do that for you. You pay expenses with cash. So, even if things look good on a spreadsheet or a financial statement, if the cash isn’t there, problems could start compounding.

Over the long-term, the amount of revenue should equal the amount of cash flow in, more or less. Likewise, the

An operating budget is important to make sure that your church stays financially healthy for the upcoming year. A financial budget is important to make sure that your church stays solvent from month to month.

One more important distinction is that a financial budget (specifically the cash budget) takes into account things that the operating budget does not. For example, capital projects, financing, and investments. I’ll illustrate the effects of these sorts of things later in the post.

How does a church financial budget differ from that of a for-profit company?

A financial budget for a church versus a financial budget for a for-profit company will differ in a couple of ways.

On the cash collection side, a lot of a church’s revenue is recognized at the same time the cash is collected. The same is not true for your typical for-profit company. The exception, for a church, might be a facilities use charges, or something similar. The timing of cash receipt and revenue recognition being so close together make the cash collection side of a church’s financial budget a little bit simpler.

The cash disbursement side of things will be similar to a for-profit company. Bills are bills after all. When expenses hit versus when they’re paid could be very different. Additionally, capital expenses, if applicable, will require big chunks of cash to be spent at one time. Just as is the case with for-profit companies. Conversely, though, income taxes are a non-factor for churches.

Other factors will be similar between a for-profit company and a church when it comes to financial budgeting. The church may still require short-term and long-term financing. Also, it may put its money into separate savings or investment account, just as a for-profit company would.

So, it stands to reason, that there are a couple of minor differences between the two. But, all in all, financial budgeting is just as important for churches, and other nonprofit organizations, as it is for their for-profit counterparts.

Why should you have a church financial budget?

The reasons for your church to have a financial budget for the coming year are the same as the reasons for doing any other step in the strategic planning process. These sorts of things are done to force you to think about what the future might hold. That way you can best position your church for success.

If your church runs out of cash midway through the year then its very existence might be at stake. Even if your church just gets into a cash flow crunch, that could start a chain of events that might keep it from realizing its full potential.

Certainly, drafting a financial budget and going through all of the steps of the strategic planning process isn’t going to guarantee that your church won’t fall upon hard times. However, it will probably lessen the length and severity of the hard times. Plus, when the hard times

One more benefit is the ability to plan long-term and short-term financing. Since these two factors play a large part in the amount of cash flowing in and out of your church, they should be scrutinized. The financial budget allows you to prepare and make arrangements for financing needs well in advance of the time that they become critical.

How to create a church financial budget

Creating a financial budget starts with a forecast of the timing and amounts of cash inflows from revenue sources. As mentioned earlier, since many of a church’s typical revenue sources are of the sort that collects cash immediately – this could be a pretty easy step in the process.

On the cash outflow side, each expense category from the church operating budget will be looked at separately. Each will be unique in terms of when the cash is expected to leave the church. Additionally, this is where capital expenditures will be entered. If you’ve done a capital budget for your church, then you should know the total amount expected to be spent. It’s just a matter of entering the timing.

The cash budget will bring together the Cash Collections Schedule and the Cash Disbursements Schedule. Also, here, you’ll be able to determine a Desired ending cash balance for every month. Beyond that, information about long and, short-term financing will need to be entered.

Everything entered previously culminates in a Pro Forma Balance Sheet and Cash Flow Statement. Along with the Pro Forma Income Statement from the operating budget, you’ll have a complete set of forecasted financial statements for the coming year. Anytime there are financial statements, you can expect there will be Ratios. The Executive Summary ends, as usual, with a chart illustrating the most relevant information from the workbook.

An opportunity is given to play with the best and worst-case scenarios. Just as was done with the operating budget. Here, you’ll have the opportunity to tweak the amounts on your Pro Forma Balance Sheet, Cash Flow Statement, and Income Statement to the positive and negative side. Accordingly, best case and worst case Ratios will also be calculated.

Timing of cash inflows

The Cash Collections Schedule is where you’ll enter the pertinent information regarding timing and amounts of cash inflows.

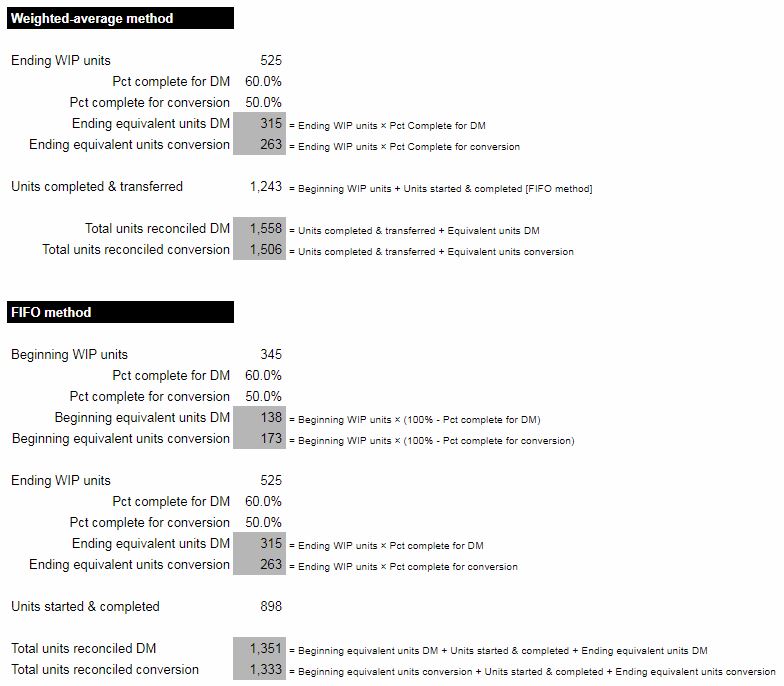

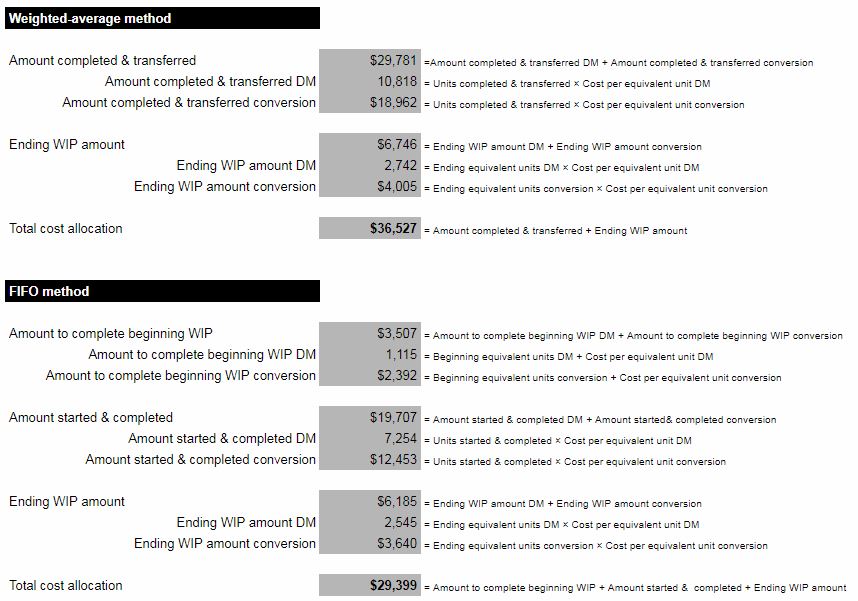

There are three general sections of information to be entered. The first is related to the timing of the receipt of Adjusted revenue sources. Here, you’ll dictate how much, percentage-wise, you expect to receive in the current month, following month,

Cash collections examples

If you expect, on average, to receive half of your revenue in cash, from your Adjusted revenue sources during the same month as the “sale,” then you would enter 50% in the % revenue collected current month field. If you expect, on average to receive the other half in the next month after the “sale” then you would enter 50% in the % revenue collected following month field. The other two (2nd following month and 3rd following month) would be 0%. What matters is the Total equals 100%.

Another example – let’s say you only took a 10% deposit for Facility use charges and collected the remainder of the balance three months later. Then, you would enter 10% in the % revenue collected current month field and 90% in the % revenue collected 3rd

Hopefully, this clarifies the purpose of these variables a little bit.

The remainder of the Cash Collections Schedule is where you’ll enter

Adjusted revenue sources

Adjusted Revenue Sources are those where the cash is collected at a different time than when the revenue is recognized.

For churches, the most practical example I could think of was Facilities Use Charges. Where the church collects cash in advance for rental of its facilities.

Revenue sources such as these, are unique, however. Most organizations recognize revenue first and then the cash is collected afterward. Facilities Use Charges are unique though. The revenue isn’t technically earned until the event for which the facilities were rented takes place. But, cash is collected in advance via deposits or payment plans.

So, the revenue for Facilities Use Charges are forecasted out three months into the following year (2020). This is done because some cash might be collected in Dec-2019 for revenue that will be recognized in Mar-2020.

Below the white cells where you’ll enter the revenue sources and forecasted amounts, you’ll see that the calculations are made based on the % revenue collected from above. The percentages entered there specify how much cash will be collected in a given month from current month revenue, following month revenue, 2nd following month revenue, and 3rd following month revenue. These amounts will change depending on what’s entered in the forecasted fields for Adjusted Revenue Sources.

Non-adjusted revenue sources

Non-adjusted revenue sources are much simpler. All you do is enter your different sources on the left and the forecasted amount for each month in the coming year. Cash is collected at the time of revenue recognition. So, there’s no need to forecast out any further.

At the bottom, the Total cash collections from revenue equal cash collection from Adjusted revenue sources plus the Non-adjusted revenue sources for a given month.

Timing of cash outflow

The Cash Disbursements Schedule is where you’ll enter information about the timing and amounts of cash outflows.

As with any organization, cash tends to leave through more avenues than it arrives. Each category of expenses (from the operating budget) is examined individually. Information from the capital budget will also be entered as it pertains to cash leaving the church.

The four categories of expenses from the operating budget are looked at independently. Granted, individual expenses within a particular category probably have different timings in terms of cash flow. But, entering each expense separately would needlessly complicate an already intensive endeavor. So, percentages are entered for each category for the % payment of current month expenses and % payment of prior month expenses.

The % payment of current month expenses refers to the percentage of that month’s forecasted expenses which will be paid with cash, in the same month. The % payment of prior month expenses refers to the percentage of the previous month’s forecasted expenses which will be paid with cash this month.

As you might expect, those percentages must add up to 100%. There’s no allocation made for expenses that will be unpaid. Since your church is reputable, and you’ve committed yourself to strategic planning (including all forms of budgeting), you’ll be well prepared for the coming year. Therefore, your church shouldn’t find itself in a situation where it can’t pay its bills.

Each category of expenses is different

The categories are pretty general. Hopefully, they are indicative of the types of expenses that your church faces. Of course, if you were making a financial budget from scratch, you might do things somewhat differently.

Once you’ve settled on the timing of cash flows, it’s time to enter the forecasted expenses for the last month of the current year through the last month of the planning (next) year. The reason that expenses are entered for the last month of the current year is because of the % payment of prior month expenses field. We must know how much cash is going to leave the church in January, because of December expenses.

The relevant cash flow amount is automatically calculated for each month and totaled by category.

Flashback to the capital budget

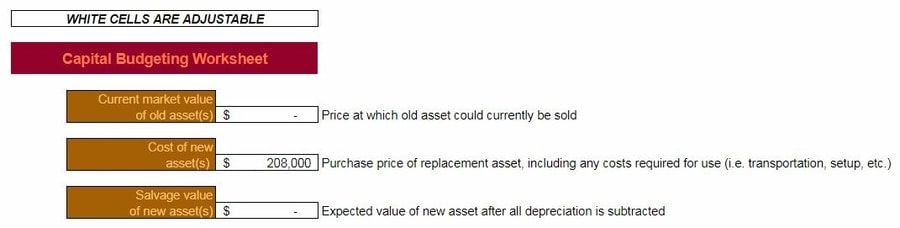

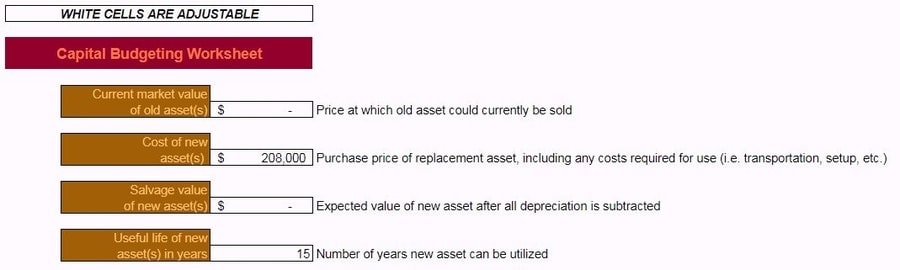

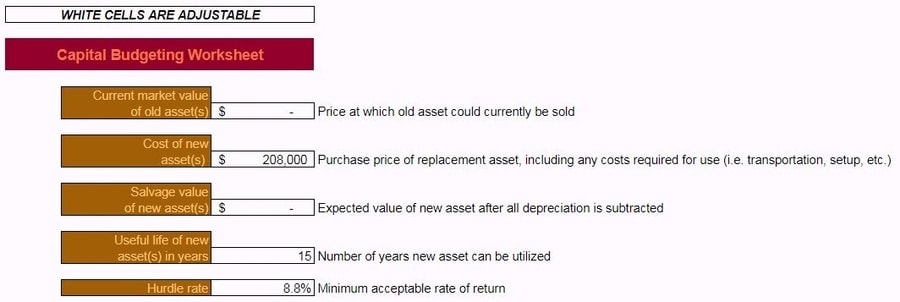

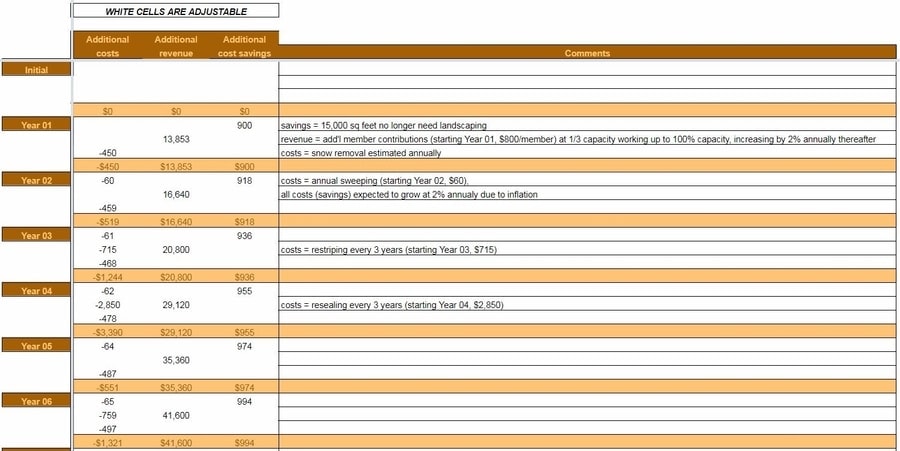

Think back to the capital budgeting for churches post that I wrote a couple of months ago. You might remember that the plan was for our hypothetical church to add 53 parking spots in the coming year. They planned to do this because the congregation was growing and they need additional capacity for parking.

You might also remember at the expected initial cost for this new

As you can see, in accordance with the capital budget, our example church expects to make three payments of $69,333. We’re assuming that, for this construction project, payment will be made in three equal portions over the three months it takes to

Our hypothetical church isn’t so big that it can disregard the spending of over $200,000. So, obviously, we needed to work that into the financial budget. The capital expenses section of the Cash Disbursements Schedule is where that’s done. This information will now carry over to the Cash Budget. This is where planning can be done for financing, if necessary.

Creating a cash budget

The Cash Budget brings together information entered in the Cash Collections Schedule and the Cash Disbursements Schedule. In addition, financing, both short and long-term are addressed; as are investments.

This is where you will forecast your actual cash balances throughout every month in the planning year. Only a few fields need to be entered. Most of what is analyzed in the Cash Budget is based on the previously entered information.

Logically, the first bit of information to be addressed in the Cash Budget is your Beginning cash balance. This will need to be entered for the first month of the planning period. You will probably have to forecast this amount if you are (as you should be) planning several months in advance. Don’t worry, as the time gets closer, this amount can be changed and, just as with any of these planning tools, tweaks can be made

From that point on, the Beginning cash balance is automatically calculated. Because, of course, the Beginning cash balance for any given month is going to be the same as the Ending cash balance for the previous month.

Cash collections and disbursements

The cash collections and cash disbursements sections will each pull from their respective Schedules – with a few exceptions.

Surplus(deficit) of collections over disbursements = Cash collections from revenue – Total cash disbursements

This amount represents the difference between cash collections and cash disbursements in a given month. A positive amount means that more cash was collected than dispersed. A negative amount means the opposite.

Notice that the months where cash payment is made for capital expenses – the deficit is rather large. This is to be expected and will be addressed more in-depth later in the worksheet.

Balancing cash

Trial ending cash balance = Surplus(deficit) of collections over disbursements + Beginning cash balance

The Trial ending cash balance represents the change in your church’s cash balance based on the Beginning cash balance, Cash collections from revenue, and Total cash disbursements. There might be situations where this amount is considerably less than you would like it to be (particularly if it’s negative). On the other hand, there might be situations where this amount is more than you need it to be. Situations where you’re holding more cash than you would like, or is necessary.

The amount of cash you want your church to hold at the end of any given month is specified in the Desired ending cash balance field. An amount will need to be entered for every month of the planning period.

This is the amount that the Cash Budget will force balance to, based on the formulas in the worksheet. Forcing is done by increasing cash with investments, short-term financing, or long-term financing. If you don’t like how the balance was forced, then you will have the opportunity to make changes later in the worksheet that

Excess (shortfall) of cash to desired balance = Trial ending cash balance – Desired ending cash balance

This amount tells you how close or far away your church is, based on the Trial ending balance, to your Desired ending cash balance.

Positive amounts will either go towards paying down debt, or it will go to an investment account. Conversely, negative amounts will either be covered with debt or will be pulled from investment accounts.

Let’s look more in-depth into financing and investments…

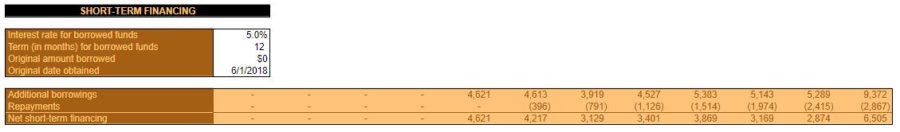

Short-term financing needs for your church

Short-term financing is a fancy term for money borrowed for less than one year. Typically, short-term financing is used for short-term cash flow issues.

In this example, we assume that the short-term financing is a revolving line of credit which allows the church to borrow moderate amounts of cash in order to cover the occasional cash flow shortfall.

You’ll also have the opportunity to enter the particulars about any existing short-term loans your church has outstanding. The rate and term entered for existing loans are assumed to be the same for any additional loans taken out through the remainder of the planning period.

Information entered for existing short-term loans is pretty straightforward. Simply enter the Interest rate for the borrowed funds, the Term (in months) for borrowed funds, the Original amount borrowed, and the Original date obtained.

Keep in mind, this is short-term financing. So the Term (in months) for borrowed funds should be less than or equal to twelve. Anything more than twelve months would be considered long-term financing.

If your church has no outstanding short-term loans, then enter $0 in the Original amount borrowed. Also, keep in mind that the Original date obtained for short-term financing needs to be within a year of the first month of the planning period in order to affect cash flow.

When will short-term borrowing take place?

As mentioned earlier, short-term financing is assumed to cover any shortfalls in cash not covered with long-term financing. It’s also not assumed to be covered with cash pulled out of investments.

The formula for Additional borrowings looks at the Excess (shortfall) of cash to desired balance, Repayments for existing short-term financing, Additional borrowings for long-term financing, and Repayments for long-term financing. If these amounts are less than zero, then additional short-term borrowing is needed.

If that’s the case, enough will be borrowed to cover the Excess (shortfall) of cash to desired balance. Repayments for existing short-term financing, and Repayments for long-term financing minus the amount that’s able to be pulled out of investments. In this workbook, it’s preferable to pull money out of investments rather than borrowing additional funds.

The calculation for short-term financing Repayments is too complicated to cover in detail. It’s calculated in a background worksheet. What this field looks at, is the Original amount borrowed, and any Additional borrowings from previous months. The total of the payments for all those short-term borrowings is displayed here. So, if additional short-term borrowings take place in a given month, the following months you will see an increase in negative cash flow due to the increase in payments owed

Net short-term financing = Additional borrowings + Repayments

This is the total effect on cash flow from activity in short-term financing for a given month. If more is borrowed than is repaid then this will be a positive amount. That’s because more cash came into the church than left it. If Repayments are more than Additional borrowings then this will be a negative amount. More money left the church than came in, due to short-term financing.

Need expert advice for managing cash flow? Read this post:

PLAN SMALL BUSINESS CASH FLOW – HELPFUL TEMPLATE & TIPS

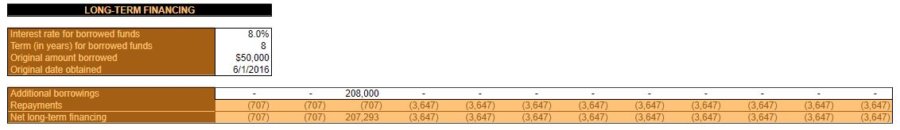

Long-term financing needs for your church

Whereas short-term financing covers borrowing money for less than one year, long-term financing covers borrowing money for more than one year. Long-term financing is typically used for long-term projects. For example, projects that have been approved during the capital budgeting phase of strategic planning.

In this example, we assume that long-term financing is used sparingly. It is not a revolving line of credit. Loans are repaid on an installment basis. Since loan amounts are typically big, Repayment amounts are also big.

Also, like short-term financing, you’ll have the opportunity to enter information about any existing long-term loans. The interest rate and term for the existing loans are the rate and terms presumed for any Additional borrowings entered throughout the year. This is unlikely to be exactly the case, admittedly, but for sake of this example, it is adequate.

For long-term financing currently outstanding, an Interest rate for borrowed funds, Term (in years) for borrowed funds, Original amount borrowed, and O

Since this is long-term financing, ensure that the Term (in years) for borrowed funds is greater than or equal to “1.” Anything shorter than a year belongs in short-term financing.

If your church currently has no long-term loans, enter 0 in the Original amount borrowed. If the Original date obtained is further in the past than the Term (in years) for borrowed funds, then the Repayments for the existing loan will not show up in this year’s cash budget. Because… of course, the loan would already be paid off.

Additional borrowings

Additional borrowings for long-term financing are (typically) only done for long-term projects. Therefore, these amounts have to be entered manually. If capital projects are being financed with long-term debt, then you would probably want the Additional borrowings to coincide, roughly with the Cash payments for capital expenses.

Repayments for long-term financing are also calculated in the background. They reflect any existing loans outstanding at the start of the planning period. Plus, any Additional borrowings taken out during the planning period are reflected as increased Repayments in the months that follow.

Net long-term financing = Additional borrowings + Repayments

Net long-term financing is the total effect on cash flow for a given month in regards to long-term borrowings. When money is borrowed, the amount will usually be positive. As money is repaid the amount will be negative.

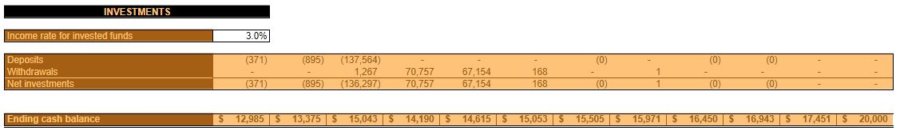

Using an investment (or savings) account

The investments account, for the purposes of this example, was created to help our hypothetical church always close the month near its Desired ending cash balance. Your church may or may not have a separate investment account, and that’s fine.

In theory, though, it wouldn’t hurt. Many times, on a Balance Sheet, cash and equivalents are grouped together. An investment account such as this might qualify as the “equivalent” to the cash that’s actually in the checking account. It is a place where you could invest excess cash that is relatively risk-free, and liquid (the term liquid, if you’re not familiar, means that it could easily be converted into cash).

Some examples of where you might park your church’s savings or investments are: money market accounts, CDs, short-term treasury bills, or something similar. The amount of return you’re going to earn on those investments isn’t going to be astronomical. But, you’re in the business of running a church, not a hedge fund. So, as long as the money is safe and earning a little bit of a return – that should be adequate.

The only field that needs to be entered in the investment section is the Income rate for invested funds. This is the annualized growth rate of monies that are in your investments accounts. The calculation for the balance in the investment account takes place in the background. It does take into account dividends and interest that would be earned in such an account. Income earned from investments is available for future withdrawals.

About the timing deposits and withdrawals from investments

The investments account looks first at the Excess (shortfall) of cash to

Since Withdrawals does not look at Additional borrowings, there might be situations where a Deposit and Withdrawal are made within the same month. A Deposit for excess money borrowed and Withdrawal to cover the Repayments.

Deposits are represented as negative amounts. This is because, technically, they come out of cash. Withdrawals are represented as positive amounts. They represent money put back into the checking account in order to achieve the Desired ending cash balance.

Net investments = Deposits + Withdrawals

This is the total amount that the cash balance has changed for a given month.

The ending cash balance

Ending cash balance = Trial ending cash balance + Net short-term financing + Net long-term financing + Net investments

Of course, as mentioned earlier, the Ending cash balance will be the Beginning cash balance for the following month. This is where the church forecasts its cash balance will end up at the end of the month. This amount should approximate the Desired ending cash balance.

*This is a long post. Click here to read Page 2.